How To Run And Write An Effective Retroactive (Postmortem)

Ever wondered how to learn from past projects or incidents? Check out this article where I break down the steps of a great postmortem. It is a simple guide to figure out what worked, what did not, and how to use these insights for your next big win. Perfect for team leaders or anyone looking to improve and prevent repeat issues from happening!

Introduction

Hi there! Welcome to our latest exploration into the world of effective retrospectives. Whether you call it a retrospective or a postmortem, I will be using the term ‘retro’ from here on out. Ever finished a project or incident and found yourself musing, ‘What just happened?’ Especially during those Murphy’s Law moments when ‘Anything that can go wrong will go wrong’? That is where the importance of a retroactive analysis comes into play, helping to prevent repeat mistakes.

Contrary to what some may think, a retro is not about pointing fingers of blame at a team or an individual, nor is it simply about pinpointing a direct cause—which I will delve into more later. Instead, retros typically involve a blame-free analysis and discussion soon after an event. They result in creating an artifact that details what went wrong and how to prevent similar incidents in the future, including an analysis of the incident response process itself.

Retros are a perfect blend of art and science, requiring honest reflection, creative problem-solving, and forward-thinking. In this article, we will explore the key components that make retrospectives not only insightful but also engaging and productive. We will discuss the best questions to ask and how to foster an environment where everyone feels comfortable contributing. Let us dive in!

Who This Article Is For

This article is for someone who is looking to improve or implement a new process to do a retroactive. If you do not have a process for retros, you should be able to almost copy and paste what is in this article and apply this to your process. Please tailor anything that is mentioned in this article to your own. You never have to mold a process to what someone says it should be, instead take the key concepts and ideas and apply those to a process that works for you.

We will not be discussing the full incident management lifecycle, but just the retro piece of it.

Basic Concepts

To ensure we are on the same page with our terms, let us define a few key concepts:

-

Retro: A process intended to help you learn from past incidents. It involves a blame-free analysis and discussion soon after an event has taken place.

-

Incident: Incident management is the process used by teams to respond to unplanned events or service interruptions, restoring operational stability.

-

Blameless: Sometimes this can be called blame-aware. What this means is you should assume everyone has good intentions. There is no need to blame anyone for a particular incident that happened. This does not mean to keep a team or person out of the conversations, it simply means to not blame them and everyone should be taking ownership. More on how to best approach this will be discussed later in the article.

-

Incident Lifecycle:

The one thing to point out here is that when an incident is resolved, it does not mean that the incident management process ends there. You need to go further and investigate the possible root cause to prevent the issue from occurring again.

- Identify: Detection of unusual symptoms signaling an issue.

- Investigate: Determination of the issue’s validity and scope. Then continue investigation of the direct cause of the issue.

- Recover: Direct cause identified and implementation of a solution.

- Closure: Formal conclusion of the incident, including a retro.

Direct Cause vs Root Cause

All incidents will have a direct cause. The direct cause is NOT the root cause. The direct cause is the event or action that took place that caused some anomaly. The root cause is how did something happened to begin with. Here is an example of direct cause:

A website went down and users started to get 503 errors. They were not able to browse any page. It was determined that the database died because it ran out of memory. To mitigate the issue, the database was restarted and the users were able to access the site again.

Direct Cause: The database ran out of memory and by restarting it freed up some memory.

We need to implement a better way from letting the database run out of memory again. You can even increase the memory, but at some point, the database may crash again and you have done nothing to prevent that from happening. By identifying a root cause, we can hopefully prevent the database from ever running out of memory again or at least better mitigate that issue from happening again.

Hopefully you are thinking that restarting the database is not enough in this case.

Before moving on. Think of some things that you can implement to help this from occurring in the first place

Here are some possible action items that you could take in this example:

- Load testing

- Increase memory

- Better alerting

- Vertically scale your database automatically

- Horizontally scale your database by sharding

- Create read-only replicas

- Implement database profiling and fix any bad queries

- Add proper indexes on tables

- And so on…

As you can see, there can be plenty of action items you can take. Until you go through a root cause analysis, you might still be missing something and not really know what you need to focus on. Once you identify the root cause, you can then make an informed decision on how far you should take your actions.

Retrospective Roles

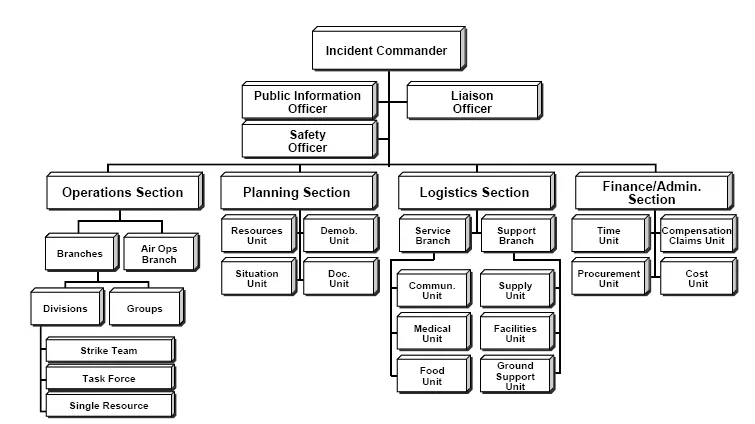

Define specific roles for an incident. Without doing this, the process may never be completed. You want to define roles that work for your company. A lot of key ideas about incident management comes from the Incident Command System (ICS). Understanding ICS helps in appreciating the roles and hierarchy crucial in incident management today, which in turn shapes the structure and effectiveness of our retros.

The ICS concept was formed in 1968 at a meeting of Fire Chiefs in Southern California. The program reflects the management hierarchy of the US Navy, and at first was used mainly to fight California wildfires. During the 1970s, ICS was fully developed during massive wildfire suppression efforts in California (FIRESCOPE) that followed a series of catastrophic wildfires, starting with the massive Laguna fire in 1970. Property damage ran into the millions, and many people died or were injured. Studies determined that response problems often related to communication and management deficiencies rather than lack of resources or failure of tactics

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Incident_Command_System

Let us define some roles that would be helpful in our incident management lifecycle.

- Incident Commander (IC) - Runs the incident and delegates out tasks. There should only be 1 IC to ensure there are not too many chiefs.

- Subject Matter Expert (SME) - There can be more than 1 SME that can help investigate an issue. There can also be more than 1 SME to help answer questions during the retro process.

- Communications Liaison - This is a person that would help communicate out to stakeholders. This could also be included with the IC responsibilities, but if you need to do communicate in a legal way, you may want to have someone write those communications.

- Incident Investigator - This is the person that will ensure the retro is completed and follow-up on any actions that need to take place to ensure that happens. There should only be 1 person assigned to this role.

Why Should You Do A Retro?

Beyond resolving immediate issues, retros help in building a culture that values and integrates learning, leading to sustained improvements and resilience over time.

During an incident response, the focus should be on restoring a service back to normal operations. No time or mental energy should be wasted in thinking about how to do something optimally or performing a deep dive on what caused the incident. Doing this could further delay remediation efforts and complicate the resolution process. That is why retros are essential. They provide an opportunity to reflect once the issue is no longer impacting users and to clearly go through the process of learning how to improve.

What Makes A Great Retro?

A great retro is one in which you learn how to improve. That is it! You might still be asking, “How do we get there exactly”? Well, let us find out together.

Retro Process

1. Set the ground rules

Establish a set of ground rules. This will ensure that everyone can follow the same process and they know what to expect.

-

Main Objective: Learn and come up with a better understanding of what happened. This would be the root cause. From here on out, I want to keep root cause out of this. I have worked as an SRE for many years now and one thing I found out is that trying to determine the root cause can be difficult for most people. A lot of people do not have any experience using the 5 Whys or Fishbone Diagrams. Plus ,these are bit old and outdated.

-

Any action items or improvements should be saved and noted until the main objective is met. This means to have a good understanding as to what happened.

-

When talking about a particular person or team and the change that was made to cause an incident, you should talk about why that change was pushed. Why did that change make sense during that time? Example: A new feature went out and your company uses feature flags, but in this case a feature flag was not used. Ask the question, “Why didn’t we use a feature flag here”?

-

Focus on how you can improve and do better next time. Stuff will break and it should be expected. Focus on how you can recover faster when something breaks or what you can do to prevent it.

-

Create a plan to follow during the meeting. An example would be to go through the entire retro first and make sure everyone agrees with the information and timeline. Then people can start to ask questions. You may also want the ability for people to ask questions during certain points of the meeting. In any case, try to make sure it is consistent.

-

Ask stupid questions. This should also be done during an incident, but seriously, ask stupid questions. There were plenty of times where I thought I knew how something worked and after asking a stupid question, I then learned how something really worked. If you are really unsure of something, ask it.

-

Get feedback on the retro. This should probably be done async after the meeting, but you or someone else might have ideas on how to better improve the meeting or something that needs more clarity.

2. Assign an incident investigator

This person should be assigned ASAP. As soon as an incident has been resolved, you need to assign this person. Depending on the organization, this person can be assigned in different ways. If you have on-call for everyone in your company, this may or may not be that person. In the places I have worked, we had teams and every team had an on-call person. If there was an issue, that on-call person would be paged to help resolve the issue, but they are most likely not the person that made the change to cause the issue in the first place.

Ideally, the investigator should be a person that can dedicate their time in driving the investigation through completion. They are trained in this area, they have a fundamental understanding of the systems in operation, and they can make people feel safe when interviewing them for more information. Sometimes this is someone from the SRE team if the organization has an SRE team.

Sometimes an organization is too small for a dedicated team of people to complete the retro. In that case, you can look at the team or person that caused the incident to begin with. Again, we are not blaming anyone here, but the person or team that caused the issue will have a better understanding as to why things happened the way they did. If it is someone new, then it should be someone else instead.

If you know the team who caused the issue, but do not know who should own it, then it should be delegated to a manager to the team that caused the issue. At this point it is the manager’s responsibility to complete the retro until they decide to reassign the retro to someone else.

If it is still unclear as to who should own it, then the IC or an SRE should own it.

3. Information Gathering

The incident investigator will begin to piece together a document. This document should be a template that is used for your organization to ensure all information is captured. You can use a Jira ticket, Google Document, Confluence, Notion, or any other tool to gather all information into one place. Depending on how you run your incidents, information about the incident may be spread across different channels of communications and tools.

Here are some areas in which you can include into your template:

Basics

Include basic information like:

- Link to incident ticket with short description (Database crashed due to lack of memory)

- Time of: Detection, Acknowledgment, Cause Identified, Mitigation, Resolution

- Roles: IC, SMEs, Liaisons, Incident Investigator

- Interviewed: People that were interviewed

Summary

Write a summary of the incident in a few sentences. Include what happened, why it happened, the severity of the incident, and how long the impact lasted for.

Think of Who, What, When, and Why.

Example

https://blog.rust-lang.org/inside-rust/2023/02/08/dns-outage-portmortem.html

On Wednesday, 2023-01-25 at 09:15 UTC, we deployed changes to the production infrastructure for crates.io. During the deployment, the DNS record for static.crates.io failed to resolve for an estimated time of 10-15 minutes. Users experienced build failures during this time, because crates could not be downloaded. Around 9:30 UTC, the DNS record started to get propagated again and by 9:40 UTC traffic had returned to normal levels.

This is an example of a public retro, but internally you should go into more detail about the incident.

Improvements:

- How many users were impacted?

- How much money did we lose from this outage?

- When did we detect the issue?

- Did we get any reports from our customers?

- Do we need to notify our external stakeholders?

Think of this as an executive summary for your VPs.

Impact

Describe how the incident impacted internal and external users during the incident. Include how many support cases were raised. If you know how much money it cost the company, this should be included as well. Include screenshots if you can. Show graphs of impact and what normal looks like.

Example

https://web.archive.org/web/20201018145502/http://yellerapp.com/posts/2014-08-04-postmortem1.html

There were two main impacts to customers. The first was processing delays on exactly 42 exceptions. Some of these exceptions took up to 7 hours to be processed and show up for users. These exceptions ran into riak write timeouts, and had to be manually reprocessed by me. The second impact was that customers could not sign up for new accounts, change passwords, reset their password, change billing or invite users to projects. That is because all of those actions require performing writes to the data store Yeller uses for user/billing information, and the capacity for that store to perform writes was disabled by the network partition.

This is an example of a public retro, but internally you should go into more detail about the incident.

Improvements:

-

If we can get an exact count of total impact users or close to it, we should use this number. A good place to find this information would be something like Datadog or Bugsnag. Sometimes a complicated db query might have to be put together to piece everything together.

-

The percentage of users can be used as well, but having a number is always better.

-

How much did this cost us? We should have made x money in this time period, but instead we made y money, so we lost z money.

-

What services were impacted?

- Was this an internal service?

- Was this a third-party service that we use?

Leadup or Trigger

Describe the sequence of events that led to the incident, for example, previous changes that introduced bugs that had not yet been detected.

Example

While attempting to make a change enabling streamlined access for our web servers to internal API endpoints (connecting directly instead of traversing our ASA firewalls), a misleading comment in the iptables configuration led us to make a harmful change. The change had the effect of preventing the HAProxy systems from being able to complete a connection to our IIS web servers - the response traffic for those connections (the SYN/ACK packet) was suddenly being blocked.

Issue

Describe how the change that was implemented did not work as expected. If available, attach screenshots of relevant data visualizations that illustrate the fault.

Example

https://github.blog/2021-12-01-github-availability-report-november-2021/

Our MySQL clusters consist of a primary node for write traffic, multiple read replicas for production traffic, and several replicas that serve internal read traffic for backup and analytics purposes. The read replicas that hit the deadlock entered a crash-recovery state causing an increased load on healthy read replicas. Due to the cascading nature of this scenario, there were not enough active read replicas to handle production requests which impacted the availability of core GitHub services.

Detection

When did the team detect the incident? How did they know it was happening? How could we improve time-to-detection?

Example

https://www.atlassian.com/engineering/post-incident-review-april-2022-outage

The first support ticket was created by an impacted customer at 07:46 UTC on April 5th. Our internal monitoring did not detect an issue because the sites were deleted via a standard workflow. At 08:17 UTC, we triggered our major incident management process, forming a cross-functional incident management team, and in seven minutes, at 08:24 UTC, it had been escalated to Critical. At 08:53 UTC, our team confirmed that the customer support ticket and the script run were related. Once we realized the complexity of restoration, we assigned our highest level of severity to the incident at 12:38 UTC.

Recovery

Describe how the service was restored and the incident was deemed over. Detail how the service was successfully restored and you knew how what steps you needed to take to recovery.

Example

https://aws.amazon.com/message/5467D2/

Initially, we were unable to add capacity to the metadata service because it was under such high load, preventing us from successfully making the requisite administrative requests. After several failed attempts at adding capacity, at 5:06am PDT, we decided to pause requests to the metadata service. This action decreased retry activity, which relieved much of the load on the metadata service. With the metadata service now able to respond to administrative requests, we were able to add significant capacity. Once these adjustments were made, we were able to reactivate requests to the metadata service, put storage servers back into the customer request path, and allow normal load back on the metadata service. At 7:10am PDT, DynamoDB was restored to error rates low enough for most customers and AWS services dependent on DynamoDB to resume normal operations.

There’s one other bit worth mentioning. After we resolved the key issue on Sunday, we were left with a low error rate, hovering between 0.15%-0.25%. We knew there would be some cleanup to do after the event, and while this rate was higher than normal, it wasn’t a rate that usually precipitates a dashboard post or creates issues for customers. As Monday progressed, we started to get more customers opening support cases about being impacted by tables being stuck in the updating or deleting stage or higher than normal error rates. We did not realize soon enough that this low overall error rate was giving some customers disproportionately high error rates. It was impacting a relatively small number of customers, but we should have posted the green-i to the dashboard sooner than we did on Monday. The issue turned out to be a metadata partition that was still not taking the amount of traffic that it should have been taking. The team worked carefully and diligently to restore that metadata partition to its full traffic volume, and closed this out on Monday.

Lessons Learned or Key Takeaways

Discuss not only what went well and what could be improved but also how these insights can be implemented in future projects. If you had to look at this retro again in a year, what would you want to know about it?

Example

https://www.honeycomb.io/blog/incident-report-running-dry-on-memory-without-noticing

It is impossible to prevent every memory leak; therefore our technical fixes are primarily focused around detection and mitigation. A high process crash (panic/OOM) rate is clearly abnormal in the system and that information should be displayed to people debugging issues, even if it is one of many potential causes rather than a symptom of user pain. Thus, it should be made a diagnostic message rather than a paging alert. And rather than outright crash and thereby lose internal telemetry, we will consider adding backpressure (returning an unhealthy status code) to incoming requests when we are resource constrained to keep the telemetry with that vital data flowing if we’re tight on resources. In this situation, it would have resulted in dropping more incoming traffic, but with the benefit of immediately getting the data we needed to diagnose the issue. Obviously, this is not an easy decision to make, and requires more discussion.

Ultimately, the main changes we need to make are to our incident process rather than technical ones. We should be more willing to believe SLO burn alerts, more willing to declare incidents, and more willing to investigate/question assumptions. We’re taking this as a lesson that consistency matters, and we’d rather err on the side of declaring an unnecessary incident than fail to declare an incident and act haphazardly. We’re promoting our user-facing SLO alerts to actually page oncall the same way our end-to-end blackbox probers do. If and when we find we’re spending too much engineer time responding to non-incidents, we will move the pendulum back a bit, and continue to iterate.

Risks

Were there any Risks identified during the incident response that were not already known? There are always risk you take based on various factors.

Example

Our application was only being deployed into one AZ within AWS, when it was thought we were deploying across 2 AZs.

Incident Handling

Describe if there were any issues while running the incident. Was it hard to get in contact with someone? Did you know who to page out? Were the roles properly assigned and people knew what they needed to do? Did it take too long to handle an incident due to a red herring.

Example

We could not get a hold of the on-call person when trying to page the DevOps team. We manually escalated the issue to the DevOps manager.

** One thing to note here, we are not trying to blame anyone if they do not answer a page, but to simply understand what happened and to improve on it. In this case it could be that the person never got the page, the person does not have their paging communications setup properly, the person got a new phone, there was no secondary setup for on-call, or whatever other reason. We want to find ways to improve this process as well.

Follow-up Actions

Document the follow-up items. Annotate if these items are related to recovery or about prevention. Sometimes an action is too complex or involved to even consider it, but it should be documented anyway. The items that can be resolved should be assigned and internal team processes should be used to complete the follow-up item.

Resources

Add any resources which may not fit in other categories, but are still important or relevant to the incident. Maybe you can add the slack channels in which all the information was gather from, the incident URL if you are using an incident management system, and whatever else.

Timeline

Detail the timeline of the incident, preferably in UTC.

Include:

- Key lead-up events.

- Start of activity and first impacts.

- Decision points and escalations.

- Theories on what could be going wrong

- Initiatives that were tried and failed to mitigate the issues

- Incident resolution and post-impact notes.

- The timings of the incident (Detection, Acknowledgment, Direct Cause Found, Mitigation, Resolution)

Example

https://www.okta.com/blog/2022/03/oktas-investigation-of-the-january-2022-compromise/

- January 20, 2022, 23:18 - Okta Security received an alert that a new factor was added to a Sitel employee’s Okta account from a new location. The target did not accept an MFA challenge, preventing access to the Okta account.

- January 20, 2022, at 23:46 - Okta Security investigated the alert and escalated it to a security incident.

- January 21, 2022, at 00:18 - The Okta Service Desk was added to the incident to assist with containing the user’s account.

- January 21, 2022, at 00:28 - The Okta Service Desk terminated the user’s Okta sessions and suspended the account until the root cause of suspicious activity could be identified and remediated.

- January 21, 2022, at 18:00 - Okta Security shared indicators of compromise with Sitel. Sitel informed us that they retained outside support from a leading forensic firm.

- January 21, 2022, to March 10, 2022 - The forensic firm’s investigation and analysis of the incident was conducted until February 28, 2022, with its report to Sitel dated March 10, 2022.

- March 17, 2022 - Okta received a summary report about the incident from Sitel

- March 22, 2022, at 03:30 - Screenshots shared online by LAPSUS$

- March 22, 2022, at 05:00 - Okta Security determined that the screenshots were related to the January incident at Sitel

- March 22, 2022, at 12:27 - Okta received the complete investigation report from Sitel

4. Interviewing Participants

While the information is being gathered, the incident investigator may need to interview people to get more clarity on the situation. As the pieces start to come together, you may find more people you need to interview about the actual events that occurred. Shoot these people a DM or try to schedule a 1-on-1 with them. Sometimes this could involve a small and quick meeting with more than one person.

-

You should determine the SMEs involved that helped mitigate and resolve the issue. This should be the first person you talk to, to get a better understanding as to what actions took place and in what order.

-

Talk to the person that made the change that caused the issue. Help them stay at ease by getting their perspective, but also letting them know that this is a learning experience and not a blame game.

-

Talk to people that have a good understanding of the underlying system or service. A developer might make a change where they thought they were fixing something, but because of some underlying tech debt, it broke something else. There may be someone with this sort of knowledge that you can talk to, to understand the tech debt.

-

This is like above in that you can reach out to former team members that owned a particular service. They might have some tribal knowledge that could be helpful during the investigation.

-

SMEs of a particular subject matter. There have been times where I talk to someone who really knows about a particular area, but they had nothing to do with the incident itself. They can shed some light on some of those technical details and why something might have happened.

Try and do things async as much as possible. This will solve time, but also respect the other person’s time. If you decide to have a meeting, try to keep it at 25 minutes.

If the person you need to interview has had no prior interaction with you before, make sure to introduce yourself first and invite them ask questions or share any concerns they have. Make sure to include details about the incident and the document you working on for additional context.

While you are interviewing someone or asking questions, keep the questions as direct and simple as possible. Ask very pointed questions in which you need answers to. Have the person you are interviewing give you the answers without guiding them.

Overall, make the person feel comfortable. This is not supposed to be an interrogation.

Some Questions You Can Ask

There are in no specific order in asking these questions, these are just examples of what can be asked.

- How were you invited to the incident?

- What did you know about the situation when you were called in?

- Did anyone address you when you joined the incident and explain the situation?

- Tell me about the order of events.

- At what point did you that X change caused this incident?

- How did you know X change caused this incident?

- What dashboards or logs did you look at and what query did you run to filter out the logs?

- Did you run any commands to determine health issues during the incident?

- Do you frequently get paged for incidents like this? How do you feel how the incident went?

- Do you have any risks or concerns that were found during the incident?

- What did you mean by “X statement”?

- Do you think you have a good understanding of the service/system?

- Do you have the proper tools needed to help you troubleshoot the issue?

- Is there enough documentation to help you understand the service?

- Were there any surprises about the incident?

Continue to get clarification where needed and again, play dumb, and ask stupid questions. You want to get their perspective and not assume anything.

After every interview, please ensure to go over what you asked and the answers given to make sure of the accuracy.

5. Review The Retro Document

By now, the document should be filled out. This will allow involved stakeholders to review the document. At this time, the document should be sent out for review and if possible, comments should be made on the document to specific individual about questions or concerns that need clarification. Make sure that things are technically correct or that your understanding of the situation is accurate.

This will also give an opportunity for people to review everything and get in a good mindset before meeting on it.

6. Meeting

The people that were involved with the incident should attend the meeting. At times, this may be difficult to get everyone in a room together and this is ok. At least 2 people that were involved with the incident should be there though. This will ensure there is enough coverage to go over the incident and ensure nothing is missing.

Also invite anyone that could benefit from the meeting. This could be people from a particular team that was dependent some service, this could be engineers that were not impacted, but still somehow related, this could be impacted users internally, management, compliance, legal, and any other relevant key stakeholders.

The incident investigator is the meeting coordinator. This means that you should ensure that all parties know what the agenda is and what their responsibilities are. You need to make sure the meeting stays on track. Remind the meeting participants to be ready to share their experience around the incident. Make sure everyone knows the ground rules. Remind everyone this is blameless and we should stay away from “what if” scenarios and to just focus on the facts. The meeting is to simply learn about what happened.

When going over what happened during the incident, this would be a good time to involve the SMEs to get a deeper understanding of the technical details. While people can ask questions, if it starts to go too far into the weeds, you may need to help keep the meeting agenda flowing.

Example Agenda

- Intro to set the tone of the meeting

- The expected agenda

- Summary of what happened to get everyone on the same page

- Overview of the timeline to ensure accuracy

- Encourage others to ask questions at this time. Again, ask stupid questions.

- What action items have been done so far

- What are next steps

Action Items

Action items should be created at the end of the meeting in the next steps. You could also create another meeting to now focus on action items, but I found that this is probably too many meetings and not enough value.

Encourage participants to hold off on any talks about remediation until the end. If someone does bring something up, then simply annotate it and let them know you will get back to it at the end of the meeting.

Once action items are defined, they should also be assigned. One way that I have done this in the past was using Confluence. I can then directly modify the document and add action items and just ”@” someone. Once the meeting has concluded, I can then convert those into actual Jira tasks.

7. Wrapping Up The Report

After meeting, you should begin to finalize the report. This should include everything that was talked about up to the meeting and any outcomes from the meeting itself. You should also add the action items that need to acted upon and maybe move certain action items to the Risks area if they will not be worked on any time soon.

Once the report is finalized, you should distribute the report. This is one of the most important steps. You need to get people to look at this report. If done correctly, everyone can learn and you are now making the entire organization smarter for doing so. This also validates all the time and effort that was spent on this. It will make future stakeholders excited to help when needed as they will feel as if the process was meaningful.

8. Wrapping Up The Retro

Once the report is completed, you may want to understand how people felt about the overall retro process. You can create a 2-3 question survey and ask for feedback about the retro process. How did it make people feel? What could be done better? Did they like the process? Did they like the flow of the meeting?

Summary

I know this was long, but it was long on purpose. I wanted to make sure that you could walk away knowing how to run through this process. You should be able to almost copy what was said in this article and make it part of your organization’s process.

I also wanted people to think of a different way to do retros. A lot of places will try and do a root cause analysis, but if you are not trained for this, it might be hard to understand. This process should be a lot simpler and more fulfilling as you are just focused on learning and improving. You are no longer worried about how to fill out a document, it should flow naturally with this method.

I hope this helps you in your journey to becoming an effective advocate for retros and building a great company culture.