Beyond Terraform and Pipelines: Unraveling the True Complexity of DevOps

Exploring the current state of DevOps and looking beyond common tools like Terraform and pipelines, this article will dig into the roles and cultural elements that define the true elements of DevOps practices.

Introduction

DevOps… It started out as this cool idea to get software developers and IT operations folks to play nice together. The goal was simple: break down the walls between them so we could get stuff done faster and smoother. But now? It feels like we just ended up swapping old problems for new ones.

I kicked off my career in IT but always had a soft spot for coding. I would sneak in a bit of automation here and there, just to make my life easier. Then, I landed a gig as a DevOps engineer. It was like finding the perfect mix of IT and coding - I was stoked.

Jump to 2024, and it is like DevOps has taken a weird turn. It is all about pipelines and Terraform now. Seems like every job I look at wants me to be a wizard with Terraform or a Kubernetes guru. But what about the big picture? It feels like we were getting a bit stuck, focusing more on these tools than the reasons we were using them.

And talk about stepping on each other’s toes - Devs and DevOps engineers are now at odds over how to deploy apps. It’s like we have built new walls without even realizing it.

In this post, I want to spill my thoughts on where we are at with DevOps today. I will break down what DevOps really means to me, look at the roles involved, and talk about why I am not exactly over the moon with how things are right now. But do not worry, it is not all bad news. I have a feeling things are starting to look up, and I will share why there is still plenty to be optimistic about.

What DevOps Really Means to Me

DevOps was supposed to be a set of practices, philosophies, and cultural values that aimed to improve the collaboration between software development (Dev) and IT operations (Ops) teams. It was designed to remove blockers and allow organizations to produce software and IT services more rapidly.

What was supposed to be a set of best practices for developing and deploying software has evolved into a role of its own, which is somewhat strange and paradoxical. I believe it is acceptable to have silos in an organization, but these silos need to communicate with each other. In my view, developers are the customers, and DevOps engineers are there to provide support. Based on my experience, I have observed that many software developers are not particularly proficient in security and infrastructure. This is not a universal truth, but a large number of software developers simply lack extensive knowledge in these areas, and I do not fault them for this. Nor do I believe they should be required to learn these complexities.

To me, what DevOps should represent is a collaborative effort among multiple teams, including software developers. They all share a common objective. The role of DevOps engineers is to ensure that software engineers do not have to concern themselves with the underlying infrastructure or security aspects. Software developers should focus on writing code and delivering features. That should be the main extent of their responsibilities. Why do they need to learn Kubernetes manifests or how to write and apply Terraform DSL code. If they require a database, they should be able to create it with all configurations already in place. Everything should be self-service without blockers, but just ensuring the proper guardrails ar in-place to allow software developers to concentrate on their primary job. If a developer chooses to venture beyond these guardrails and explore on their own, that is also acceptable. They might not receive immediate support, but we should still assist them in achieving their goals.

Provide a golden path that software developers would love to walk down, not a path in which they have to follow.

Exploring the Roles within DevOps

Let’s dive into the roles that I believe encapsulate the full DevOps experience. I have intentionally left out discussing the security team in detail, although it is vital to note that a robust security team is essential in the DevOps framework. Ideally, this team should operate independently under different management to ensure the best practices are maintained, providing effective checks and balances.

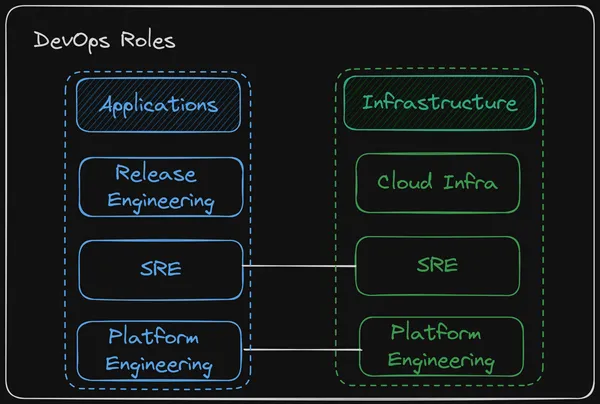

We should begin by looking at the distinction between Application and Infrastructure functions. You can think of these as Software Engineers vs System Engineers. I have separated these because they seem to aim for two different targets. The Application side is more about honing in on the continuous integration process, whereas the Infrastructure side tends to focus on the continuous deployment aspect.

What do these roles entail in practice? Let us examine some of their responsibilities to gain a clearer picture.

Applications

-

Release Engineer: This role is all about managing the release of new software versions. They ensure there is smooth coordination between development, QA, and operations teams for seamless and timely releases.

-

DevX Engineer/Platform Engineer: Their job is to make the developers’ lives easier. They do this by streamlining workflows, enhancing tooling, and ensuring developers have everything they need to be productive and efficient.

-

Embedded Site Reliability Engineer (SRE): This role focuses on guaranteeing application reliability and fine-tuning performance. They handle monitoring, performance tuning, capacity planning, and automating operational tasks. Additionally, they work closely with developers to incorporate best practices for stability and efficiency into the development lifecycle.

Infrastructure

-

Cloud Engineer: Experts in cloud-based infrastructure, these professionals manage cloud resources and work on optimizing cloud services for better scalability and cost-effectiveness.

-

Platform Engineer: They are responsible for building and maintaining platforms that support both development and operational activities. Their work includes managing cloud environments, container orchestration systems, and server infrastructure.

-

Site Reliability Engineer (SRE): This role ensures that applications are deployed reliably and run smoothly in production. Their focus areas include infrastructure automation, monitoring, fostering a positive culture, and responding to incidents.

You might wonder why a platform engineer cannot do the same as a cloud engineer, or why an SRE cannot cover all these aspects. There is no clear-cut answer. It does not necessarily mean that you must have a separate team for each function. Many of these roles overlap. As a company grows, you might find distinct teams for each function emerging. In a smaller setup, one team with a mix of these skill sets might suffice.

From a customer-facing perspective, and here the customers are the developers, it is beneficial to present a unified front. It simplifies support processes and reduces the need for extensive management layers.

Now, regarding having two types of SREs and platform engineers. I know it might not make sense, but let me try to explain.

Embedded SREs lean more towards performance issues and operate similarly to software developers. They know their services inside out and can be the go-to experts. They can manage on-call duties for their specific services, build run books, and generally improve the developers’ experience.

Infrastructure SREs, on the other hand, are more involved with incident management, retrospectives, culture building, and handling major incidents as incident commanders. They are also there to troubleshoot issues, fine-tune the infrastructure, and ensure its performance and reliability. These SREs are more aligned with the systems engineering aspect.

You do not have to take just my word for this. Even Google differentiates between SRE Software Engineers (SWE) and SRE Systems Engineers (SE).

So, what differentiates the types of platform engineers?

Here, too, the roles can be shared among multiple individuals. You might have someone focused more on software engineering and another more on systems engineering. The software side of platform engineering might involve building common tools across all services, ensuring code quality, enhancing the development process, and contributing to building an Internal Developer Platform (IDP).

A platform engineer with a systems engineering focus would concentrate more on the infrastructure platforms on which applications are deployed. In the context of Kubernetes, this might involve developing a more efficient Kubernetes deployment process, possibly by building operators and integrating them into the IDP.

Finally, a cloud engineer would primarily focus on the cloud infrastructure. For example, if using AWS, they would manage the accounts and underlying network infrastructure.

As you can see, while you can define boundaries across these functions, the ultimate goal is to assemble a team capable of handling all these responsibilities. By doing so, you can truly live up to what DevOps is meant to be.

Ultimately, this is where my frustration stems from. In my experience, many who bear the title of DevOps engineers seem to concentrate primarily on aspects of release engineering and cloud engineering, often halting at the boundaries of platform engineering. It’s not uncommon to find a company with a dedicated DevOps team covering these specific roles, while a separate SRE team handles the rest. However, there are instances where the DevOps team is also expected to take on SRE responsibilities. In such cases, this dual role is frequently not managed as effectively as it could be. The distinction becomes blurred and often leads to neither domain receiving the full, specialized attention it requires.

This overlap and the resulting underperformance in specialized areas is a significant part of my concern with the current state of DevOps. The original ethos of DevOps was to bridge gaps and enhance efficiency, but this can only be fully realized when each role is allowed to focus on its strengths and core responsibilities.

What Is Wrong With Terraform And Pipelines

For those of you who have been working with Terraform for a while, you’re likely familiar with the types of challenges it can present. As your network grows in complexity, scaling and managing Terraform becomes increasingly difficult. The typical solution? Scale up the number of people who are proficient in Terraform. However, the reality is that most Software Engineers (SWEs) are not particularly inclined to learn or engage with Terraform.

Now, should you use Terraform? Absolutely, yes. Or at least, adopt any tool that enables you to implement Infrastructure as Code (IaC). For AWS users, CloudFormation or CDK might be more appropriate. And if you’re looking for something akin to CDK but with multi-provider support, Pulumi could be your go-to. My point isn’t that Terraform is inherently flawed, but rather, as you stabilize your infrastructure, it becomes critical to reevaluate and possibly improve how you manage the state of your resources.

Then there’s the matter of pipelines. They can be quite finicky and prone to breaking. Do you often encounter flaky tests? How straightforward is it for you to perform a rollback, deploy a hotfix, or handle long-running tests? Is your team capable of deploying multiple times a day? With Continuous Integration (CI), the goal should be to make each step idempotent and as fast as possible. One of my main frustrations with CI tools is the difficulty of testing certain steps without committing code, which seems rather absurd. You should be able to replicate these steps locally. Regarding Continuous Deployment (CD), embracing GitOps is a wise move. Nowadays, managing your deployments as a state, similar to how you handle Terraform, is straightforward and effective.

In summary, while Terraform has its place and value, there is always room for improvement. As a DevOps engineer, you should not stop here. Let’s delve into how we can enhance these aspects in the next section.

Moving Pass Pipelines And Terraform

So, what do we turn to if Terraform isn’t our go-to tool?

I’m seeing Platform Engineering as the next big step in the evolution of the DevOps role. Picture this: using Kubernetes as a control plane for managing your resources. When you start treating everything like an API, you open up a world where you can define anything, either imperatively or declaratively. This can be seamlessly integrated into your Internal Developer Platform (IDP) with just a click, yet still maintain the flexibility of pushing changes via GitOps.

Ever used platforms like Heroku, Cloud Foundry, Railway, Fly.io, or Netlify? They make code deployment a breeze. However, they come with their limits and can be pretty rigid in how they want things done.

Here’s an example to illustrate my point. Imagine you have a service that includes:

- A frontend service running on Node.js.

- A backend service in Golang, functioning as a REST API.

- A database using AWS RDS.

- Elasticache for search functionality, since it’s an e-commerce site.

- Redis for caching.

From a developer’s standpoint, what steps are needed to set up and deploy all these components? Let’s say we are using Terraform with a pre-defined module for these resources. The developer needs some Terraform know-how to get started, but beyond that, we could assume automated deployments. But what if they want to upgrade their database? How is that handled?

Up to this point, there is nothing wrong per se. Assuming everything is streamlined and fully automated is an achievement in itself. But, if you are familiar with Terraform’s limitations, you will realize it is not as simple as tweaking a few values in a file.

Now, let us reimagine this scenario with Kubernetes operators building a real platform. A developer hops onto the IDP, selects or creates their service, and specifies the desired services and dependencies. They no longer need to fuss over Terraform or Kubernetes manifests.

Behind the scenes, a Kubernetes operator manages these resources. Take the RDS database, for example. If you configure the operator appropriately, it can manage the entire lifecycle of the RDS instance, including safe deletion for ephemeral environments. Try doing that with Terraform modules using IaC. You would need to do a destroy command on a target and that is a little scary.

Upgrading your database, especially with significant changes like new parameter groups, becomes more straightforward with an operator. Even complex tasks like blue/green database deployments become feasible. This is still hard to do, but possible.

What about manual changes causing state drift? The operator auto-reconciles these changes in minutes, keeping everything in sync.

I could go on about the benefits of operators over Terraform, but here’s one final thought. Operators allow you to deploy resources in the same way as your applications. Using tools like Helm and ArgoCD, you can create Helm charts for these resources and manage them through ArgoCD.

In my view, being able to deploy anything consistently, without juggling a dozen different tools, is a game-changer. Even if you are not using Kubernetes to deploy your services, I still thinking using a Kubernetes control-plane for infrastructure resources still has many advantages.

Conclusion

As we wrap up, if you are a DevOps engineer, it is time to take a step back and think about how you can elevate your game. How can you offer even better support to your developers? Remember, having silos is fine, but becoming a roadblock is not. If your ticket backlog is growing and developers are constantly waiting on your support, that is a red flag. It is time to reevaluate your approach. Move beyond familiar tools like Terraform and start embracing tools that foster a more robust platform approach. There is a lot of potential and room for growth in this area, and getting comfortable with creating and using new tools should be on your radar. This might mean learning a bit of Golang. You do not have to build everything from scratch, but do n0t shy away from it either. Embrace emerging tools like Qovery and Crossplane, get to know them, and integrate them into your workflow. Do not stop using Terraform and traditional pipelines, but just look to improve those processes. You may want to manage your underlying network infrastructure (VPC, Subnets, Gateways, etc…) and this is perfectly fine. Your developers still do not have to touch Terraform code and these are things that will probably not change very often, which makes it easier to manage.

And here is something to look forward to - keep an eye out for a future blog post where I will dive deeper into these innovative tools and explore the exciting possibilities they bring to the table. There is a lot of positive momentum in the world of DevOps, and I believe we are on the cusp of some truly transformative changes. Stay tuned, because the best is yet to come, and I cannot wait to share these developments with you.